In June 2014, Santiago Cirugeda and Jorge “Bifu” Barroso announced the closure of La Carpa (the big top) in downtown Seville. It had been four years since the radical architect and theatre director had teamed up to assemble the city’s first self-built independent arts space by occupying a disused piece of public land.

And so the structures that made up La Carpa – by now, a popular fixture in the city, with its own circus group – were dutifully taken down: two second-hand circus tents, a two-storey building made from shipping containers, a skate ramp, and the iconic araña – another container, this one mounted on four, half-bent metal legs like a post-nuclear spider (certainly not your average office space).

La Carpa was never really intended to be permanent, yet its creation required extraordinary self-sacrifice. Barroso, director of the Varumatheatre group, spent a year living onsite (in the araña) to secure their claim to the land: “It was pretty tough,” he recalls. “I had no electricity, no water, I was being robbed every couple of days – it felt like I was in prison.”

The occupation allowed them to gain a preliminary land concession from authorities, and from there, La Carpa began to grow. By the time it closed, Barroso estimates tens of thousands had attended concerts, theatre performances, live music and workshops there.

In many ways, La Carpa bears all the hallmarks of the practice Cirugeda has run for the last decade: Recetas Urbanas is known all over Spain as a reference for low-cost, self-build projects that need the expertise of someone used to navigating – and often exploiting – Spain’s complicated planning bureaucracy. This is what Ciruegda does best: “I get a kick out of the confrontations with technocrats and politicians,” he says, “but most of all I like building my own projects … in Seville, the crisis affects us all, we are in a desperate situation and there’s a lot of injustice in the way things are being done. What about all these empty houses and unused land? There are lots of situations that interest me – as an architect and as a citizen.”

The backdrop to Cirugeda’s work is Spain’s economic crisis, during which 500,000 half-built properties have been abandoned, while hundreds of thousands of Spaniards unable to pay their mortgages have been evicted from their homes under draconian repossession laws.

But even as a student in Seville, years before the crisis, Cirugeda was setting out to be a very different kind of architect. “From the beginning I wanted to experiment,” he recalls, “so I started doing projects out on the street.”

In one of his first experiments, Cirugeda applied for a standard skip license. There was a house nearby undergoing works, so the permit was granted. But Cirugeda wasn’t intending to actually hire a skip to dump rubbish. Instead, he built his own, complete with the standard orange and white stripes but topped with wooden boards – and a centrally mounted seesaw. He called it “a self-built and self-managed urban playground”, and it proved hugely popular with the younger residents of the Alameda, the former red-light district where he lives and works.

Guerrilla Architect, the first in Al Jazeera English’s Rebel Architecture series.

Within a few days however, a neighbour had complained about the strange structure, and Cirugeda was summoned to the local police station. The planning authorities, however, were forced to concede that he had met all of the legal requirements; he had requested a license, the skip was clearly marked and it didn’t obstruct the traffic or pedestrians. There were no other legal grounds on which to challenge the installation, so the project continued, moving to different locations around Seville, reappearing with a swing, as a small flamenco stage and as a theatre set for a group of local kids. Later, for another project, he knocked down the walls around plots of unoccupied municipal land and reused the swings and seesaws to create itinerant play parks – all this in a city that had only one public playground at the time.

This is the sort of project that Cirugeda’s practice has pioneered: playful, resourceful, legally provocative but most of all, highly functional. Aesthetics, on the other hand, take a back seat. “People say my architecture is ugly,” he says, not looking in the slightest bit offended. “They say it’s interesting, but it’s ugly – but I say, who doesn’t have an ugly friend? Everyone has an ugly friend! Architecture today is obsessed with beautiful buildings and pretty projects – that’s bullshit! Architecture should be cheap, functional and it should be an excuse to bring people together: and that’s what we’re doing.”

In austerity-stricken Spain, Ciruegada is by no means alone in advocating collective self-build projects. As well as Alice Attout – his partner and fellow architect – Recetas Urbanas counts on a support network of dozens of so-called “collective architects” all over the country (La red de arquitecturas colectivas). Its members work on different projects across Spain, but in recent years they have also started to collaborate on self-build projects, helping social or activist groups by joining forces and resources.

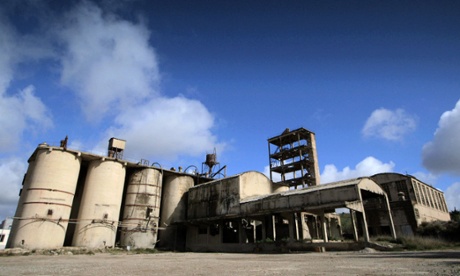

The Fábrica de Toda La Vida – on the site of an abandoned, Franco-era cement factory in the south-western city of Badajoz – is one such project. When a group of local artists and graduates wanted to turn the factory’s derelict warehouses into artists’ studios, they turned to Cirugeda. Recetas Urbanas made the case to local authorities that by propping up the crumbling factory roof, they were saving a piece of heritage. It was an argument that convinced authorities to grant the collective a temporary concession to the warehouses.

They have since been joined by architects from Barcelona, Madrid and Seville and an irregular stream of volunteers – from architecture interns to a professional chef to other groups who’ve previously worked on self-build projects with Cirugeda or his colleagues in other places. Diego Peris, an architect from Madrid who runs the Todo por la Praxis studio says this is a different way of using their profession “Usually architecture is very hierarchical, very top-down; here, it’s different, everyone gets involved.”

In Spain, where architects are among the young professionals most affected by mass unemployment, and the profession is implicit in the spectacular boom that preceded the bust, Cirugeda and his fellow “collective architects” are trying to redefine the possibilities for architecture. In 2013 they launched a website that offers guidelines on how to occupy and lay claim to abandoned municipal land, circumvent planning laws, and how to build basic structures, all using previous projects as case studies. But according to Peris, “what we’re doing here is not a quick-fix to the crisis – this is about finding alternative ways of doing things.”

Certainly, the acute years of the crisis have allowed activist groups and collective practices to come into their own, seizing the space left by the rapidly retreating state and taking advantage of its inability to intervene. Self-build projects and occupations are occurring all over Spain. But assuming this space on the margins of the law and of the state has its price.

“I rent an old house that used to be a brothel, I drive a second-hand van, and apart from that I don’t own anything at all,” Cirugeda says. “There’s no money in this.

“Wouldn’t it be easier to have a normal job, to go into an office every day and get paid? … Maybe – but it wouldn’t fulfil you. When you’re laying down the nuts and bolts, with your friends, you get an immediate reward – and something grows out of it.”

Ana Naomi de Sousa is the director of Guerrilla Architect, which airs on Al Jazeera English. The film is the first in the Rebel Architecture series:@RebelAchitecture